A mottled brown even when new, although I never saw it new. It sat behind those strange glass doors that lifted up and then slid back into the dark oak bookcase on Summit Street. The box was rarely opened. It was as mysterious as the empty rooms way up on the dark and vaguely scary third floor, where nobody lived although I knew that Elmer once had.

A mottled brown even when new, although I never saw it new. It sat behind those strange glass doors that lifted up and then slid back into the dark oak bookcase on Summit Street. The box was rarely opened. It was as mysterious as the empty rooms way up on the dark and vaguely scary third floor, where nobody lived although I knew that Elmer once had.

And this is the house that held the box that held the papers that held Lena’s memories. With its Queen Anne turret and brown shakes, it always seemed both exotic and safe. It had a formal front door but I only remember going in through the kitchen: the warm steaming kitchen… where the coal stove was enormous, the table was covered with oilcloth., and the long strips of pared-away pie crust spiraled down from a stubby knife.

Built in 1880, the place still stands. But Mary, Carrie and Jo Lennon, who lived on the second floor – the independent spinsters with their shiny ribbon candy and sugary Easter eggs enclosing vistas – that trio is long gone. I had always thought they were the landlords but in fact it was the McVeys who lived in the house behind. Lennon, McVey, Donath, Flaherty… these are the friends of Lena that I remember. All Irish although she herself was a Russian Jew. Mom explained this by saying that Lena – unusually – had not come from some Jewish shtetl but had lived among non-Jews in Russia and so that’s how she was comfortable. I now know most everything my mother told me was wrong.

I don’t believe this was deliberate. Mom was the baby, born 14 years after Lil, her eldest sibling. In the way of these things, I’m sure it was Lil who revealed to my mother the lives before her life. And then my mother told me. It was, precisely, a family game of Telephone, distortion after distortion. All informed by the hazardous era my mother grew up in. In the thirties and forties, to be Jewish often meant you were marked to die.

Beryl was one, Grandma Lena’s lost beloved brother.  A young doctor, he was called out on a case and never came back. The next morning he was found floating in a canal, murdered. It was suggested that was the reason that Lena had run away, by herself, to America. Mom had no aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents from that side of the family. Lena had left them all behind. She was fourteen years old and had come to a place where she didn’t know anyone. I was always impressed by that. Sixty years later, while dying, in her final lonely bed, she cried for her father. It was probably Lil who said so, font of misinformation, but that I believe is entirely true.

A young doctor, he was called out on a case and never came back. The next morning he was found floating in a canal, murdered. It was suggested that was the reason that Lena had run away, by herself, to America. Mom had no aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents from that side of the family. Lena had left them all behind. She was fourteen years old and had come to a place where she didn’t know anyone. I was always impressed by that. Sixty years later, while dying, in her final lonely bed, she cried for her father. It was probably Lil who said so, font of misinformation, but that I believe is entirely true.

I also believe I knew there were letters in the brown box, letters from the Old Country. Lena may have been a religious reader of Reader’s Digest — we both devoured Humor in Uniform –; but I knew those spidery words on yellowing paper were in Yiddish, their writers all swallowed up by the black maw of history. Beryl couldn’t have written them. Beryl was long dead. And I didn’t know any other names.

Except for Dorothy. Dorothy: the child who haunted my mother’s childhood. An older sister who never got older than eight or nine. She had died before my mother was born. At some point, I was told her young life had been cut short by diptheria. Both my brother David and I have an unreasonable fear of suffocation, maybe from this story — from that tenacious gray membrane across the windpipe. Or maybe it was from our mother’s frequent bouts of pneumonia, her cracked ribs, her hacking breathlessness. I have no way at this point to be any kind of sure.

But then Lena died and Peish – with his long yellow teeth — came to stay with us. David B — who ought to know — says he was a depressive but I mostly remember his grin.

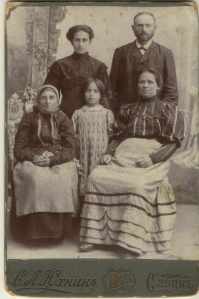

Amid the chaos and grief, however, it soon became clear he was now demented. I barely noticed when the brown box appeared in my headboard. I did open it though. I opened it and found this photograph:

The child in the middle looked familiar. She could have been me. I believed at that moment that this was my grandmother as a young girl. Again, as in everything, I believed wrong.

And then Lena was buried and the rains came down and I wept to think of her lying all alone in that wet earth. But I went back to school and the brown box disappeared. And then life got in the way: school in California, work, marriage, children. And then other deaths: Peish, Elmer, Lil, and finally my mother. I was now the oldest girl… though that didn’t really register for a long while. There was so much cleaning up to do.

Sybil, a child of the Depression, could not throw away anything. Stashed in the house were thousands of plastic bags, swaying nests of containers from the long-gone Newport Creamery, dozens of metallic mesh purses from the local Whiting & Davis factory outlet. Hats. Shoes. Thirty-four pairs of white cotton gloves. Handkerchiefs and scarves. The rotting suitcase from her honeymoon sixty years earlier. I lugged it out to the street for the garbage men … and the tattered lining split and letters slid from their hiding place. Love letters from my father when he was away at sea. There were also stacks of postcard written by boys during the War. She was the home front beauty they were all fighting for. And then finally – half-buried by boxes, envelopes and folders — the mottled brown box reappeared. I opened it. The young girl who could have been me stared out with her half-familiar half-smile. But she was a mystery I now had no way of solving. Everyone was dead. All lines to the past were broken. I closed her inside her pasteboard tomb again.

* * * * *

I only realize now that it was actually before my mother’s death that I found my first key to Lena Land. In 2002, I was researching David Duke and reading Troubled Memory by Lawrence N. Powell. It tells the story of Anne Skorecki Levy, a resident of Warsaw who was four years old when the Nazis marched in. She survived the ghetto hidden in a chest, saved only by her perfect silence. And yet when the racist, antisemitic Duke was on the verge of being elected governor of Louisiana, her new home, she overcame a lifetime of conditioning to speak out against him and foil his campaign.

At the front of the book there is A Note on Polish Pronunciation. I read there:

“The sz is pronounced as the English sh, as in Leshno (Leszno)

The cz is pronounced as the English ch, as in Chista (Czyszte)”

A silent depth-charge went off in my brain. My grandmother had always claimed she came from a town called Shemisaville. At least that’s what it sounded like to me. I thought it was a joke, like the Yiddish word Yenemvelt that means someplace really far away from here. Like the Yiddish word shmendrik that means a nonentity, a backwater jerk But by that point I had found what I believed to be her Ellis Island manifest.

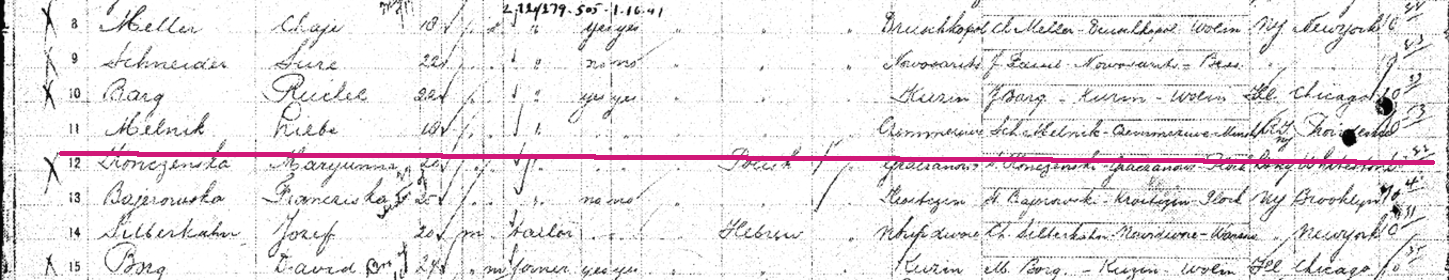

In 2002, Steve Morse’s site was the only viable search engine for those huge handwritten manifests, and Melnick — meaning “miller” — was not exactly an uncommon name. But Lena had once given me a treasured Indian head penny from 1890 so I knew for sure that’s what her birth year was. Still I searched a long time in vain because I had been told she arrived as a 14-year old. Only when I expanded the date of arrival and the spelling of both first and last names, did I find a Liebe Melnik from Czemmeziwe, born in 1889-1890 and 18 on arrival, who was bound for Providence to visit a cousin named Leon Braicinesky. A cousin is precisely whom family lore said she’d come to see! The name Braicinesky, however, did not ring any bells. Nor did the Inez Court this “cousin” supposedly lived on. I could not find such a street on any Providence map.

I knew a lot got lost in the mis-translations at Ellis Island. I also knew desperate immigrants were not above flat-out lies. The given was that my grandmother had no relatives this side of the Atlantic. All my mother’s cousins, uncles and aunts came from her father’s line. How could there have been a cousin right in Providence that I had never heard of, let alone laid eyes on? Unless, of course, the man had died. So Leon Braicinesky got filed away under Missing in Action and I turned to the entry for her birthplace and last known residence: Czemmeziwe It had long been Sanskrit to me.

Until… A Key to Polish Pronunciation unlocked that stream of consonants: Czemmeziwe was Shemmezive! A small window opened in the dark.1

Or actually many windows. Plugging Czimmeziew into the Shtetl Finder — whose actual name is the JewishGen Jewish Communities Database –, yielded 3 hits in the Ukraine… except that Lena hadn’t come from there. Because Peish often referred to her as his Little Litvak, I long assumed she was from Lithuania.

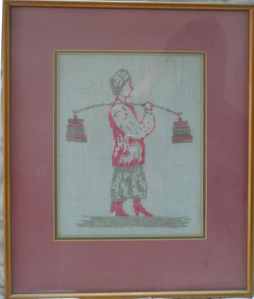

But at some point, I was given by Soph a framed piece of linen  with a typewritten note taped to the back of it: LENA MELNICK WOVE THIS LINEN AND EMBROIDERED THIS DESIGN ABOUT 1905 IN A TOWN NEAR MINSK IN WHAT IS NOW CALLED WHITE RUSSIA. IT WAS A PILLOW CASE FOR HER TROUSSEAU. SHE CAME TO THE UNITED STATES IN 1906. SHE MARRIED PHILIP BLISTEIN IN PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND ON 12 SEPTEMBER 1909. SHE WAS 19 YEARS OLD.

with a typewritten note taped to the back of it: LENA MELNICK WOVE THIS LINEN AND EMBROIDERED THIS DESIGN ABOUT 1905 IN A TOWN NEAR MINSK IN WHAT IS NOW CALLED WHITE RUSSIA. IT WAS A PILLOW CASE FOR HER TROUSSEAU. SHE CAME TO THE UNITED STATES IN 1906. SHE MARRIED PHILIP BLISTEIN IN PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND ON 12 SEPTEMBER 1909. SHE WAS 19 YEARS OLD.

Even though by the time I saw this, I knew she had in fact emigrated in 1908 and the wedding date was September 21st and not 12th, I saw no reason to doubt that she had come from somewhere near Minsk in what is now called — not White Russia — but Belarus. Alas the database for Belarus showed no hits for Czimmiziwe. I then recalled my mother’s fervent belief that her mother had not come from a shtetl at all, but from a “Russian” town with only a few Jews in it. I turned to the JewishGen Gazeteer which cast a wider net. It turned up four towns. One immediately jumped out at me: Semezhevo. It wasn’t the closest to Minsk. Dzenisovo had that distinction; but Semezhevo looked exactly like the name Lena had said.

Semezhevo is actually a fairly well-known place in the Belarussian scheme of things. You can find pictures of its famous Christmas pageant all over the Web. But only when I stumbled on an Angelfire site called the “Mestechki of Minsk Gubernia”, did I feel confident that Semezhevo was the place Lena had fled

The “Mestechki” (©2000 Michael Steinore) was extracted from a gazetteer published in 1909. It contained “all (113) towns with the administrative designation mestechko from an original list of over 14,000 settlements in Minsk Gubernia. A mestechko was the settlement type most synonymous with a shtetl. Many Jews in Minsk Gubernia lived in these mestechki (plural), though they certainly lived in settlements with other administrative designations too, primarily the gorod (city) and selo (village).” So I was back to the shtetls again.

The beauty of the Mestechki list, however, was that it not only listed the shtetls, and their populations, but also the nearest railway station, and the district or Uzed in which they were located. Semezhevo was located in the Uzed of Slutsk. This led me back to JewishGen and its Yizkor books, compiled by Holocaust survivors to rebuild on paper their vanished homes and families. And in the Yizkor book for Slutsk, there was an entry for Shemezheve. It was written by Sonia Kashdan, whose father Yekhiel had been the feldcher (barber-surgeon) for the town.

Yes, it was in Yiddish and I had not yet begun to study Yiddish, but Google Translate and I took a stab. If you locate it now on JewishGen, you will see I have been given a translation credit. In fact, I submitted a badly mutilated version which some kind soul corrected and restored to its original poetry. Even in those early days, however, armed only with Google and my copy of Weinrich’s New English-Yiddish, Yiddish-English dictionary, I was able to read the first sentence: “In my village of Shemezeve, there was a population of 2,000 peasants while the Jewish population was extremely small”. The next sentence specified: “there were only 25 Jewish families.”

Corroborating this, I found a web site titled The History of Belarussian Jewry. It listed the Jewish and gentile population of Slutsk’s shtetls per the official census of 1879. There were 88 Jews in Semezhevo, out of 2,538 total residents. This presumably was why I hadn’t been able to find it in the Jewish Communities Database. It wasn’t by any definition a Jewish Community. Lena had grown up surrounded by non-Jews.2

I suppose it barely needs stating that the Internet has become an immense and living organism. It crouches at the edge of our collective consciousness, sometimes malignant, sometimes benign. And growing, always growing, fed by ever-increasing infusions of data. As would become a regular habit, I plugged this new Semezhevo/Shemezeve into Google. And watched, with tightening gut, as the name Lejba Melnick churned up.

My first reaction was shock, then delight. Maybe now I would learn something. And then fear. Why fear? What exactly would be learned? A past that had seemed sadly but safely closed, a world contained entirely within my grandmother and the void into which her family vanished… now spilling out, into Moscow of all places. Images of gangster relatives in velour leisure suits arose unbidden. As bizarre as their thinking I drove a Cadillac and carried ivory-handled guns.

I studied this group of Semezhevo Melnicks, spelled Melnik, though of course it was all transliteration. Of six siblings who would have been Lena’s contemporaries, three died in the twenties, in their twenties, sadly young. Two had no known date of death. This probably meant they had been lost in the Holocaust. There was only one who died of old age and left at least one heir behind him. Boris Melnik, like my grandmother, was a solitary survivor of a once-large family. The twentieth century’s stunning calculus of death.

I wrote to the man who had posted these Melniks. His name was максим матвеев (or Maksim Matveev). Boris seemed to be his grandfather. He wrote back immediately. He’d had trouble with the JewAge website and was in fact Boris’ great-grandson as it turned out. Could we be related? How could we not? With only twenty-five Jewish families in the shtetl, could two have had the same name and not be from the same line? Our relatives were millers, there was a mill (though my mother had described it to me as a factory) Maksim had been told it had been partitioned among siblings. Boris’ father was named David; Lena’s had been named Samuel. We posited they had been brothers. But as we exchanged information and photographs, things got really weird.

For one, Maksim claimed that Boris’ sister — named Lipa — had emigrated to the US in 1907. There was also a brother named Leibe, which — despite Lena’s manifest — he informed me was not a girl’s name. Even stranger, Maksim had a family story about a young doctor called out on a case and murdered, except his name was Isaac and it had happened long after Lipa’s departure. Isaac’s body had been found in Vashki, near Leningrad, in 1928.

We began to wonder if the cousins were so close they had considered themselves siblings. Maksim’s source of information had been papers left behind by his great-aunt Eugenie, so there was also the possibility she had confused some names. I sent him the one photograph I had of Beryl but he was adamant that this was not the murdered Isaac. It was also not his great-grandfather Boris. Considering that I spoke no Russian and Maxim no English, it is pretty amazing that we could communicate at all.

And then Putin invaded the Ukraine; and Maksim and I found ourselves at odds politically. Our correspondence faltered and finally stopped. I was left with some photographs, his site on the Russian JewAge, and a lot more mysteries. I decided it was time to learn Yiddish and open the box.

1My brother David has protested that I should have read Czemmeziwe as Chemmezive which of course — if this were Polish — would be literally correct. But I already knew the name of the town and was just trying to reverse-engineer this manifest. Also, it assumes that the poor clerk at Ellis Island had an easier time transliterating Shemezeve than he/she did Leon Braicinesky (about which more later)

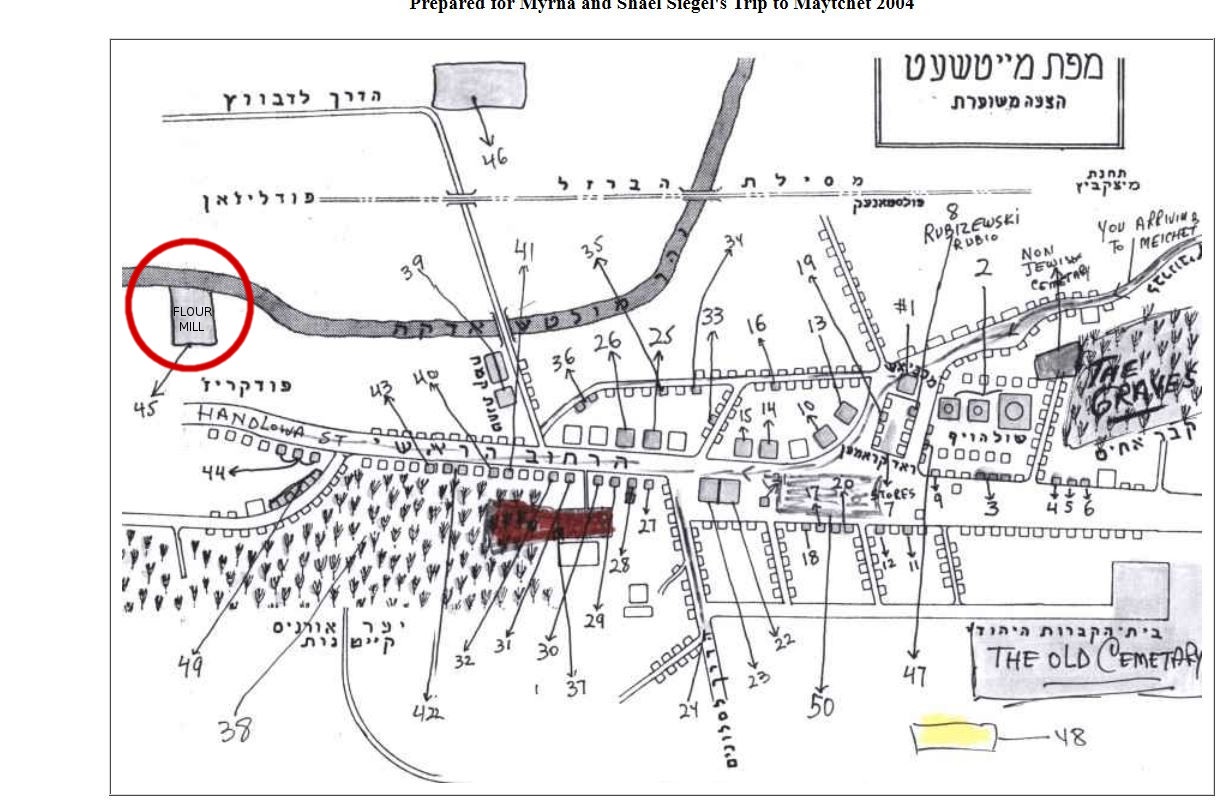

2Much later, I found an essay by David M. Fox about his family’s mill in Kolodozi, Minsk Gub., which includes the line: “As with most mills, they were not located in towns or shtetls, but on the outskirts near a river or stream.” So apparently Lena grew up not only not surrounded by Jews, but also not surrounded by anyone else.

memory map of Maytchet — another Belarus shtetl — with its mill on the outskirts of town